Desmond Tutu

The Most Rev’d Desmond Mpilo Tutu, Archbishop Emeritus: A personal memoir about a ‘Father’ and a friend

The Feast of St Stephen, 26th December 2021

Ever since the current Archbishop of Cape Town announced the death of Desmond Tutu early on Boxing Day, the many tributes being paid often begin with words such as activist, campaigner, protester, fighter or opponent. And then they go on to a whole list of issues and -isms, such as apartheid, racism, sexism, campaigning against oppression on grounds of colour, gender, age, sexual orientation, or for basic human rights, or the liberation of oppressed black and coloured South Africans, women, LGBTQ – and adding ever more letters and words recently – and then continuing with the right to die and assisted suicide, since his own supportive statement of 2016. While these are all true, sometimes it seems as though Desmond Tutu has become a blank screen upon which anyone can project their own issues, passions, pains or concerns.

Yet these popular descriptions miss the heart of the person that I knew over more than four decades, someone who insisted on ‘being’ before ‘doing’, contemplation before action, or who said he wanted to be a ‘quietist’ more than an activist. When first trying over 40 years ago to arrange his daily schedule, I quickly learned that he needed to spend hours in silence and prayer before he could speak, in ‘taking in from God’ before ‘giving out to people’, in thought and contemplation before campaigning or making pronouncements.

Over these years, never a year went by without at least me making one visit to the Archbishop, whom I quickly learned to call ‘Father’ in the traditional but simple respect for the priesthood. Whenever we met, the first thing he would do (after enveloping me in a bear hug) was to insist on joining together with him in a prayer before talking.

The same was true of any journey with ‘the Arch’ in a car or taxi; after the driver got over the shock of seeing in the rear-view mirror who his famous passenger actually was, would come the regular request – ‘please, before you start driving, let us pray – for care, for safety, and for others on the road’.

This combination of joy, genuine affection and deep spirituality has characterized all my dealings with Archbishop Tutu.

I first met him in person in May 1990. I became Chaplain to Exeter University in the late 1980s, and immediately tried to invite Archbishop Tutu to come and give a special lecture on his belief in God’s ‘moral universe’ – but for years the political authorities refused him a passport. When he was finally able to come to Britain, it turned out his visit would be on the same day as the first formal face-to-face negotiations of Nelson Mandela and the ANC with F.W. de Klerk and the apartheid government back in South Africa.

Suddenly, this catapulted him to the top of Britain’s security list, lest any incident with him here might jeopardize the peace discussions back home. At London Heathrow, the early morning plane was kept ticking over and passengers still seat-belted while armed police brought him and his wife, Leah, to meet me in VIP security for immigration. Despite his insistence on the priority of the Eucharist, there was no time for it as we raced in armoured cars to Reading Station where the train was (inevitably) delayed.

When we finally got on board, the poor steward who asked me for our breakfast order was confused when I asked for a small bottle of red wine and a slice of bread as soon as possible. ‘Bread for everyone?’ ‘No, one piece of bread.’ ‘Shall I cut it up for you?’ ‘No, the Archbishop will break it.’ And his final despairing attempt to help: ‘Would the Archbishop like it buttered?’! As we celebrated Holy Communion with police protection at 125 mph, I marvelled at this mixture of spirituality and modernity as the Lord was present to us in the Eucharist and prayer for the state of the world.

During that first visit, I was amazed by Tutu’s stamina, his joy, his ability to give totally of himself in his public speaking and his personal conversations – but with the unseen but constant need also to withdraw, to be quiet and to pray. I witnessed how the public life was sustained by his spiritual discipline.

At the end of that long and tiring first day, I told him that he was doing a live interview on BBC Radio 4 at 7am before then presiding at the early cathedral Eucharist. He calmly announced that he needed waking up at 4.30am for his prayer and meditation – and his morning jog. The image of armed Special Branch officers running alongside the diminutive figure in his episcopal purple tracksuit in the early morning mist along the River Exe, followed by prayer and the sacrament, and a demanding radio interview, remains with me still today: the physical and the spiritual, the public and the private, the political and the religious, all united in this extraordinary man, my ‘Father in God’.

After being involved with his first ‘retirement’ (as Archbishop of Cape Town) in 1996, I was invited to spend a couple of months in Cape Town with Archbishop Tutu while he was chairing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 1998. I was undertaking research on his theology for a book about how the Bible was used under apartheid. His commitment to the principle of ‘justice’ for all is well-known, regardless of race, colour or the ‘shape of their nose’ (his frequent example to provoke laughter at his own expense – although he also used this example seriously in Rwanda, where Hutus and Tutsis have different shaped noses).

It was often asked whether his sense of justice arose from a political ‘theology of liberation’. This had first begun in South America among the poor communities oppressed by right-wing military regimes – and was viewed with suspicion, even by the church, as being too ‘communist’; but it quickly spread to many different situations of oppression, from women’s lib to gay rights and all today’s various issues.

Was the apartheid regime’s accusation true that Tutu was at heart an atheist or communist who twisted theology and Bible in that light? Indeed, his commitment to the ‘struggle’ and to ‘liberation’ is seen as early as 1964 in a letter to the Dean of King’s College London, asking to stay on after his undergraduate degree to be allowed to take a master’s: ‘I would, I think, want to have a shot at it. In a sense it is part of the struggle for our liberation. Please, I hope it does not sound big-headed or, worse, downright silly. But if I go back home as highly qualified as you can make me, the more ridiculous our Government’s policy will appear to be to earnest and intelligent people.’

During the 1970s, teaching theology back in South Africa, followed by working for the Theological Education Fund (based in Bromley, Kent, where I found echoes and memories of that time when I was a curate there in the 1980s), brought Tutu new ideas – but his former tutors at King’s College met his enquiry about doing a doctorate on ‘black theology’ with blank incomprehension!

Tutu came across the concept on his first visit to the USA for a conference in New York in 1973, at which it was suggested that this was a political phenomenon based on racism, especially in the southern states. Tutu gave a paper arguing against ‘black’ as a negative meaning ‘non-white’ or ‘non-European’: ‘the term ‘black’ has been quite deliberately adopted so that we can describe ourselves positively. It is an assertion of our personhood’ – so he set out to give it an African setting, drawing on ideas of ubuntu in the Nguni language, or botho in Sotho. This was explained by the Archbishop in the Johannesburg Star as early as 1981. So is that the explanation of what drove this ‘turbulent priest’ – just another politician in a dog collar?

In 1982, Tutu’s understanding of justice was twisted against him. The Eloff Commission, appointed by the apartheid government to investigate the South African Council of Churches (SACC), of which Tutu was then the general secretary, accused him of being an atheist and communist. But here we see that his constant stress on the dignity of all human beings was in actual fact deeply rooted in his faith and his reading of the Bible. He began simply: ‘I want to show that the SACC and its member churches have their agenda and their programmes in this matter determined by what the scriptures have revealed as the will of God, the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ’. His detailed defence statement was full of biblical quotations and scriptural references.

A year later, his contribution to the collection, Apartheid is a Heresy (1983) was also predominantly a Bible study, arguing that ‘apartheid contradicts the testimony of the Bible categorically’. Similarly, his eight-page rejoinder to P.W. Botha in March 1988 is packed with more scriptural references, and states: ‘The Bible and the Church predate Marxism and the ANC by several centuries… Our marching orders come from Christ himself and not from any human being.’

At the twenty-fifth anniversary service to celebrate Tutu having been consecrated as the first black bishop in South Africa, his elderly mentor from the monks of the Community of the Resurrection (based in Mirfield, Yorkshire, but with a distinguished history of service in southern Africa), Father Timothy Stanton preached that: ‘Those were the days of Liberation Theology, Black Theology, African Theology, Contextual Theology, but it’s not from the exponents of these that the Archbishop quotes. The only book that the Archbishop quotes from extensively is the Bible.’

However, this essential commitment to the biblical principle of the love of God for everyone, regardless of status, colour, race, gender, age, orientation, or even ‘the shape of their nose’ is constantly there in Tutu’s beliefs and message right from the start. He has often told me the story of being an eight year-old urchin on the streets of Sophiatown (outside Johannesburg) who was amazed to see a young priest in a soutane ‘doff his wide-brimmed clergy hat to my mother’. That a white Englishman could wish his beloved mum, ‘Good morning, Madam’, had a huge impact on the young Tutu, giving him that ‘sense of the unique worth of a person as a beloved child of God’.

This understanding was then further reinforced through his early experiences serving at the daily mass with Archbishop Trevor Huddleston (who visited him daily when he had TB in his early teens) and other clergy of the Community of Resurrection. Huddleston also famously gave Tutu’s childhood friend, Hugh Masekela, his first trumpet. Masekela went on to be as much part of the soundtrack of the struggle for liberation as the Arch’s sermons.

It is this basic but iron-clad belief which enabled Desmond Tutu not just to survive the beatings, tear-gassings, insults and other extraordinary pressures, but to go on declaring and demonstrating to others the love of God for everyone, a love which he renewed through the basic principle that each day must begin with prayer and meditation, worship and the sacrament. I remember one morning we were celebrating the daily Eucharist with his team at the offices of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, when lawyers from P.W. Botha arrived with a legal writ for Archbishop Desmond. He just carried on with the liturgy – while John Allen, his public relations adviser took them aside to explain that ‘God was more important to the Arch’ – and whatever divine aspirations P.W. might have, they would just have to wait.

In 2004, I hosted Archbishop Desmond and Mama Leah for three hectic months at King’s College London, during which I chaired a three-way dialogue between Archbishop Desmond and the Chief Rabbi of Great Britain, Jonathan Sacks, and the Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams. Archbishop Rowan and the Chief Rabbi carefully picked their way through the various ‘minefield’ questions that their staff preferred us to avoid but, sitting between them, Archbishop Desmond threw caution to the winds, asserting his basic belief in ‘the unique worth of everyone as God’s children’ with his typical humour and great enthusiasm. At one point, he suddenly threw his arms wide open to demonstrate the universality of God’s love, shouting ‘God loves ALL!’ – only to knock his distinguished dialogue partners clean off their chairs.

Sadly, I was not able to visit him or attend his birthdays in 2020 and 2021 (his 90th!) because of the pandemic, so my last visit was to join in the (not quite so early these days) daily communion for his 88th in 2019, followed by breakfast with the rest of his family, children and grandchildren. He recorded a brief personal video to be shown at the dinner to celebrate my own ‘retirement’, stepping down as Dean of King’s after 25 years to concentrate on my research and writing. Yet his message was the same as always, concluding by telling us, ‘Thank you, thank you, all of you, who have been such marvellous, marvellous role models’ in not being ‘hoity-toity’ (a typical Tutu-ism!) but making other people ‘feel so special, as if you were the only student to be cared for’ – ending with, of course, his infectious, giggling laugh, a wonderful echo of that anonymous English priest who made his mother feel ‘so special’.

Desmond Mpilo Tutu was a man who had seen great sorrow and suffering, both of his beautiful yet torn and divided land, and in his own illnesses and persecutions. Yet he remained always a person of great joy, humour, encouragement – with irrepressible laughter and the ever-constant hug and a smile, but always rooted in prayer and the sacrament. In this very special child of God, the divine combination of inward retreat and outward activity, of prayer and politics, of suffering and joy, of tears and laughter, was brought closer to perfection than in any other human being I have met, a mix of spirituality and humanity which made it a joy to be able to call Tutu, ‘Father’.

An edited version of this tribute is available at The Spectator.

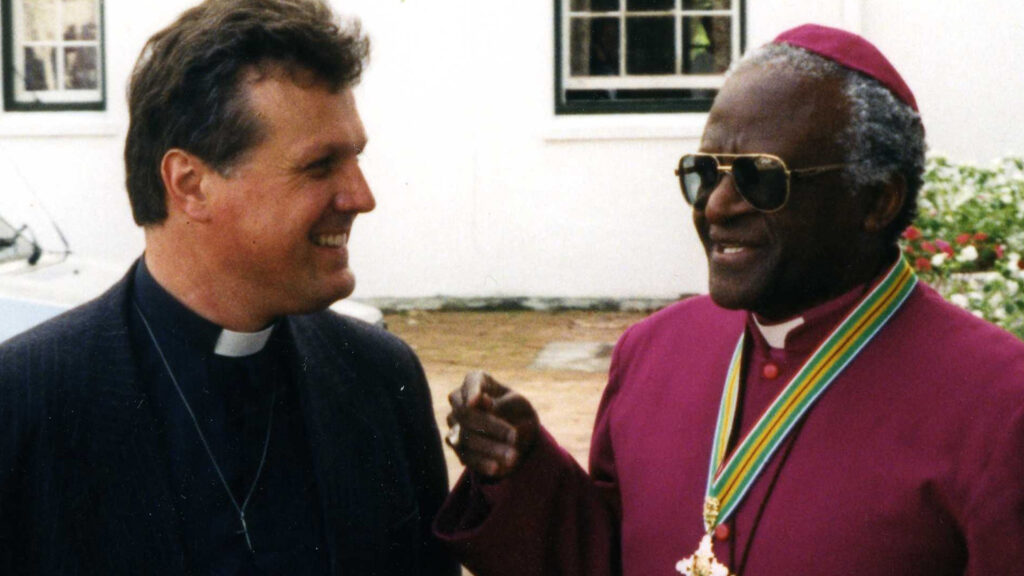

Top photo: At Richard and Archbishop Desmond’s last eucharist together on the Archbishop’s 88th birthday.