‘Doing theology on his knees’: Joseph Ratzinger

Following the recent death of Joseph Ratzinger / Benedict XVI, here is my tribute and assessment of him, originally published in a shorter version in The Tablet, https://www.thetablet.co.uk/blogs/1/2301/-doing-theology-on-his-knees-benedict-xvi-s-biblical-scholarship

The music swelled to a crescendo as the clouds of incense drifted up into the golden dome of St Peter’s Basilica, threatening to obscure the huge lettering, “Tu es Petrus”. It was December 2005 and I was one of only two non-Romans attending the Second World Congress for the Pastoral Care of Foreign Students alongside hundreds of Catholic university chaplains from all over the world.

As the representative of the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Anglican Communion, I was honoured with an audience with Pope Benedict XVI at the end of the service. Having been introduced to the Holy Father by a Cardinal Archbishop from the Philippines in his accented Italian, I began, as a courtesy, to address him in German to pass on Archbishop Rowan Williams’s Christmas greetings. Hearing my terrible accent, he immediately responded in much better English. Later I wondered if it would have been better if we had all just conversed in Latin! But it raised the important issue of translation, which is crucial for understanding Ratzinger as a theologian of the Bible.

In 1943, the young Ratzinger was conscripted at the tender age of 16 at just the same time as Pius XII promulgated his important encyclical, Divino Afflante Spiritu, which first encouraged Catholics to use historical criticism and the original languages in biblical studies. However, Ratzinger’s experience after the war as a young seminarian of the German Form-Critical methodology (which dominated European scholarship for most of the middle of the twentieth century) was not a happy one. As he later wrote in his introduction to the first volume of his Jesus of Nazareth (2007, pp. xi-xxiv), for him historical-critical scholarship separated the “historical Jesus” from the “Christ of faith” with the result that “the real object of faith – the figure of Jesus – became increasingly obscured and blurred”.

In a movingly personal comment, he lamented that “intimate friendship with Jesus, on which everything depends, is in danger of clutching at thin air”. He described his three-volume biography of Jesus as “my personal search ‘for the face of the Lord’ (cf. Psalm 27:8)”. This personal commitment to the figure of Jesus within the life of the Church dominated his attempt throughout his life and ministry to translate critical study of the scriptures for Christians today.

It also empowered his youthful energy and passion for the gospel and for the church. Those who only know his reputation from his later life as the hardline “Rottweiler” or the “Panzer Cardinal” would be surprised to meet the younger Joseph Ratzinger, who used his clearly brilliant mind to try to move things on after the war and to find positive results from the dominant German Form-Critical methodology.

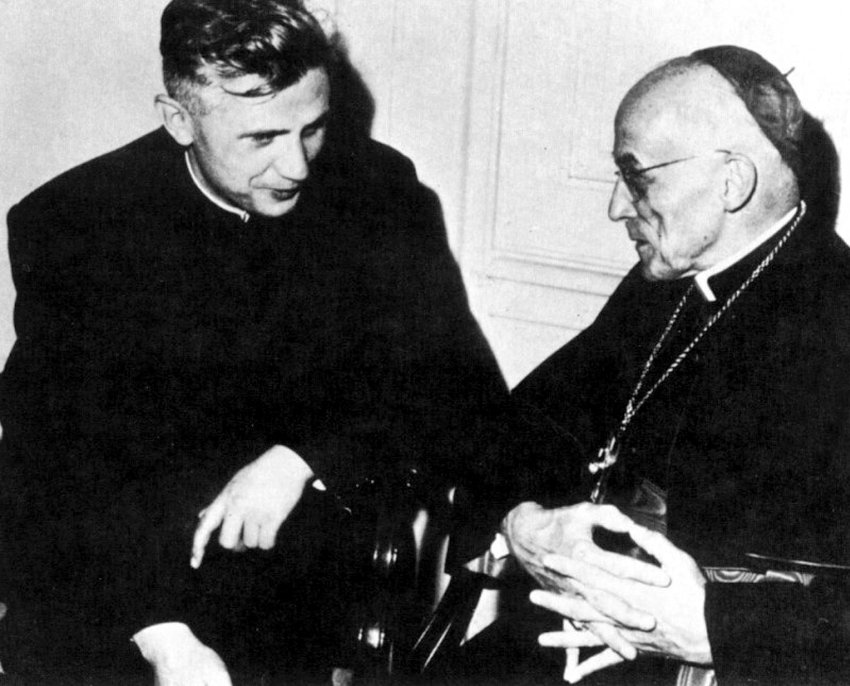

After a swift rise as a young professor in Germany, Ratzinger acted as a peritus, or theological adviser, to Cardinal Frings, Archbishop of Cologne, throughout the years of Vatican II, working from the start particularly on the highly contested decree about the Bible as the Word of God, Dei Verbum. The arguments were so bitter that, although it was one of the first topics to be debated, it went through no less than seven different versions before becoming the very last document of the Council, promulgated by Pope Paul VI only a few weeks before it ended.

Throughout, despite his own painful experience as a seminarian, Ratzinger worked tirelessly against the conservatives’ attempt to condemn historical critical methods, as he later chronicled in his detailed 1969 commentary on the document, including analysing all the drafts and the debates. Painstakingly tracing the different versions, identified by the letters A to G, and which bits of which draft made it into the final promulgation is an even more complex set of literary relationships than the Synoptic Problem (where there are usually thought to be only four sources, even if one is labelled further down the alphabet, at Q!)

The decree begins with the statement that revelation is per Christum, Verbum carnem factum, “through Christ, the Word made flesh” (DV 1.2) – and this sets immediately this major theme for understanding Ratzinger’s Christological reading of the Bible, which has to be properly founded on both critical scholarship and the life of the Church. However, the decree also goes on to affirm that God, as well as being the author and originator himself, chose and employed human agents as authors in the real or “true sense” with all “their powers and human faculties”, which means that we need our critical faculties to ascertain what the scripture writers “really intended to signify”, which includes paying proper attention to the genera, the literary forms or “genres” (DV 3.12).

One problem which dogged the later use of the document was the choice of the word ‘forms’ in the official English translation to translate genera in the original Latin version – which was often taken to mean the same as in ‘Form Criticism’. However, while Form Criticism was essentially destructive and reductionist in its interest in the ‘forms’ of individual passages (pericopae), more recent genre studies have shown that proper attention to the literary ‘form of the whole’ document or, more properly, its literary genre is crucial both for the composition and later interpretation of any text – and especially the gospels. We are back to my opening experience in my audience with Pope Benedict of the importance of translation in any human communication.

This twofold commitment – to both the intellectual life and the Church – explains Ratzinger’s later development, which some interpret as merely a shift from being a “liberal” in the 1960s to a “conservative” later. The reality is much more complex and interesting than those easy labels suggest. It is true that the maturing Joseph reacted against what he saw as the liberal excesses of the later 1960s and its cultural revolution. Nonetheless, that constant desire to hold together good biblical scholarship about Jesus of Nazareth with the faith of the Church in him as Christ is what drives Ratzinger from the young seminarian and theological “expert” at Vatican II through to the strictures of the later Pope.

This is best seen, perhaps, in his crucial 1988 Erasmus Lecture in New York for the Institute on Religion and Public Life, publishers of the American Catholic journal First Things. In this, Ratzinger delivers a blistering critique of the form-critical approaches of earlier German scholars such as Bultmann and Dibelius, without retreating into an obscurantist fundamentalism; instead, from a philosophical and theological perspective, he called for a new partnership between biblical exegesis and systematic theology. This theme recurs throughout his subsequent works, such as his Preface to the important 1993 Pontifical Biblical Commission document, The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church, and his 2002 L’Osservatore Romano article on the Catechism of the Catholic Church, in which he states that “the living Christ is the genuine norm for interpreting the Bible.”

On becoming Pope, Benedict used his first homily in the Lateran Basilica on 9 May 2005 to stress the call of the Church to preach Christ through scriptural study. This was followed by a conference on “Sacred Scripture in the Life of the Church” on the 40th anniversary of Dei Verbum in September 2005. The first Synod of Bishops which he convened, in October 2008, led to his post-Synodal Exhortation on the Word of God, Verbum Domini, which not only reflects the title of Vatican II’s Dei Verbum, but describes how “the Council emphasizes the study of literary genres and historical context as basic elements for understanding the meaning intended by the sacred author”. Here at last, they are using the correct English translation of ‘genres’, rather than ‘forms’.

Meanwhile, Ratzinger began writing his own account of Jesus of Nazareth during the summer of 2003; following his election as Pope in 2005, he gave “every free moment” to working on it until he published the first volume in 2007. Here, he stresses that the historical-critical method “is and remains an indispensable dimension of exegetical work” but also that we need “a Christological hermeneutic which sees Jesus Christ as the key to the whole” (pp. xv-xix), within what he calls “canonical exegesis”, the role of the Church as the “People of God”. He concludes: “I believe that this Jesus – the Jesus of the Gospels – is a historically plausible and convincing figure” (p. xxii).

True to his academic background and his commitment to the historical-critical method, this volume is based upon wide reading particularly of German biblical scholars, though less so of British or US scholars, which is unfortunate, not least since he would probably have found the work of people such as Graham Stanton and myself on the importance of literary genres, especially the biographical genre of the gospels, more congenial than that of his compatriots! Unfortunately, the pressures of the papacy meant that the two subsequent volumes, Holy Week: From the Entrance into Jerusalem to the Resurrection (2011) and The Infancy Narratives (2012) were less scholarly-based, and more of a collection of spiritual meditations upon the biblical text.

The following year the Joseph Ratzinger Foundation picked up these two themes of “Historical and Christological Research” on the gospels for its large annual Symposium and invited me to give the opening keynote address, prior to being honoured as the first non-Roman Catholic to receive its prestigious Ratzinger Prize for 2013. My doctoral work on the literary genre of the gospels had been previously translated into Italian in 2008, and celebrated with a major international conference in the Catholic Faculty of Theology in Barcelona in 2012 on the twentieth anniversary of its first publication.

An initial plan was to conclude the symposium with a debate between Pope Benedict and myself about the gospels and their biographical picture of Jesus of Nazareth, but unfortunately this was precluded first by his decision to resign, and then by ill-health during the conference itself. However, in his citation at the Presentation Ceremony in the Salla Clementina in the Vatican, Cardinal Ruini told Pope Francis that the award was because my work had restored “the indissoluble connection, both historical and Christological, between the gospels and Jesus of Nazareth” (in particolare un grande contributo al riconoscimento, storico e teologico, del legame inscindibile dei Vangeli a Gesù di Nazaret). In his response of congratulations, Pope Francis noted that “Benedict XVI did theology on his knees”.

As a previous prize-winning Laureate, I am invited every year to the the Ratzinger Prize ceremony – and Pope Francis often returns to this theme of Ratzinger’s combination of theology with spirituality in the annual address that he gives. This was true again in early December, when I attended this year’s ceremony which included the first Jewish laureate, Prof Joseph Halevi Horowitz Weiler, a human rights lawyer who had fought to maintain the presence of crosses in Italian schools. In his address, Pope Francis drew attention to the sixtieth anniversary of the opening of the Second Vatican Council and how Ratzinger had “personally participated as an expert and played an important role in the genesis of some of its documents”. Poignantly, one of the last public photos of Benedict XVI shows him meeting with this year’s winners.

This combination of theology with spirituality, ‘doing theology on his knees’, sums up perfectly all that I have been trying to argue about the man himself and his work in this piece. It was a great honour to have an audience with Pope Benedict right at the start of his pontificate and to receive the Ratzinger Prize named after him at its end – but even more so, to share with him a passion for academic biblical study about Jesus and the gospels to enrich the life of the church.

May he rest in peace after his labours for the gospel – and rise in glory!